With FSMA’s risk-based approach to food safety and GFSI certifications de rigueur for processors to sell to retail chains, processors need to bring their employees up to speed on best practices for food safety techniques to meet regulatory requirements, obtain GFSI certification(s) and produce a safe product. But training has often been an open-loop system, with employees hearing lectures and seeing training videos on proper procedures, and maybe asking questions and getting responses. Too often, employees don’t get the feedback on how well they’re doing their jobs—nor in many cases, do they have their procedures properly explained and performance evaluated according to an objective, predefined measurement system.

Recently, a study designed and conducted by Robert Meyer and sponsored by Alchemy Systems revealed that processors, with a little effort, can build closed-loop systems that help employees achieve nearly perfect performance in their roles, improving product quality and food safety. The study, The Positive Impact of Behavioral Change on Food Safety and Productivity, looked at food worker behavior compliance at four major processors and how the combination of effective training, corrective observations and coaching improved both food safety and productivity.

The purpose of the study was to determine if prescribed supervisory coaching coupled with effective training could drive employee performance among front-line food workers. The study consisted of three phases:

-

Identify the production process that needs improvement and then determine what standard should be used to measure effective performance.

-

Parse the identified standard into a sequence of process steps, and break down each step into a sequence of effective behaviors.

-

Supervisors conduct corrective observations using detailed compliance checklists. In cases of noncompliance, corrective actions are assigned.

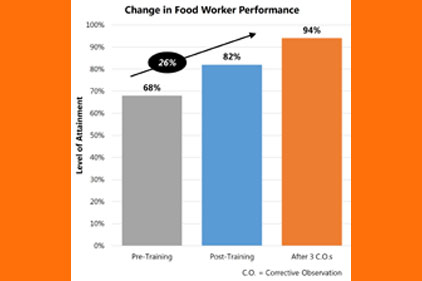

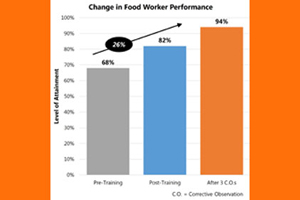

The study found the closed-loop system (the combination of effective training, corrective observations and coaching) can improve safety and productivity by up to 26 percent, averaged across the four large plants participating in the study: a soup/sauce plant in California, a meat processing facility in Wisconsin, a Missouri cheese/dairy operation and an Illinois meat production plant.

The study outlined a specific process or corrective observation model for achieving sustainable behavioral changes that result in improved food safety, productivity, efficiency, workplace safety and the process itself. The steps include: deconstructing process steps, determining desired behaviors, establishing a behavior baseline, providing targeted training, discovering and providing corrective observations, and driving continuous improvement.

The study described a corrective observation evaluation scale in which levels of performance were matched with levels of coaching and recognition of employees. Corrective observation checklists were developed and tailored to specific applications at each food plant. In each of the four plants, employee behavior, along with food safety, production performance and efficiency, and plant safety, improved markedly through training with corrective observation. The results for each plant were akin to improving a letter grade of C- or D to an A or A+.

Often, poor training is indicative and a predictor of other issues. “There is a strong correlation between training and safety issues,” says Laura Dunn Nelson, Alchemy Systems vice president of technical services & business development. If a processor is struggling with GMPs, productivity issues and customer complaints, there’s a direct correlation that it hasn’t effectively trained its staff. “In other words, if you see a plant that struggles in executing its training program, other key operational concerns will be present, including food safety and workplace safety noncompliances,” says Nelson.

What’s needed, according to Nelson, is a training program that encompasses workplace safety, food safety and HR training, leveraging all the training resources a company has. “We understand there’s only a finite amount of time for training, so instead of departmental staff in silos training on these topics separately, what if departments were to work together on these topics throughout the year? Taught hand-in-hand, you would have a superior program.”

For the complete, online exclusive interview with Laura Dunn Nelson, visit www.foodengineeringmag.com/behavioralchange